our history

Our History

HOME was founded in 1971 to fight discrimination in housing access. Many of our victories are well known, setting Supreme Court precedents and providing national impact.

When Thomas Jefferson crafted the Declaration of Independence, these words were adopted:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness… That to secure these Rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed…”

Yet all men were not created equal.

It wasn’t until President Abraham Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 that persons held as slaves were considered equal.

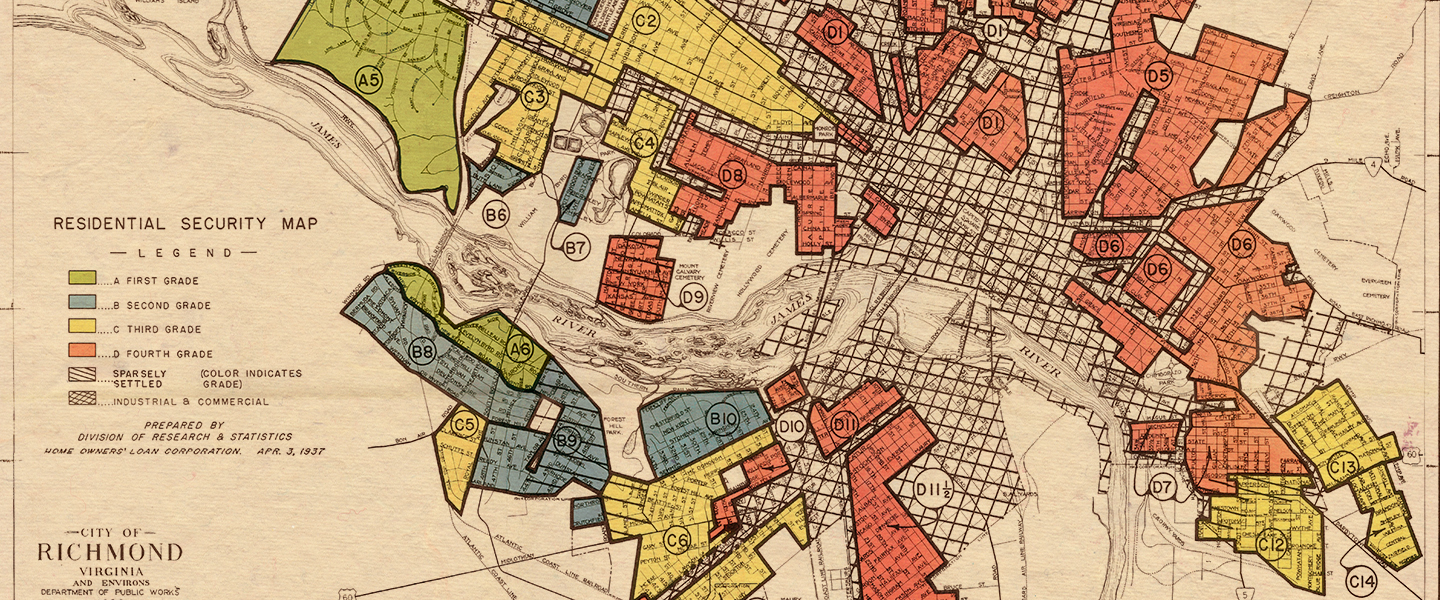

Despite this, from Lincoln’s time through 1917 a series of laws made it easier to discriminate based on things like race. The “Jim Crow” laws allowed under Plessy v. Ferguson allowed discrimination in housing, schools, work, travel, and daily life. In 1917, the Supreme Court ruled that zoning ordinances requiring segregation violated the 13th Amendment. While this slowed discrimination, land and property owners devised restrictive covenants that got around barriers to discrimination.

The Civil Rights Acts of 1964 prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, or national origin in places of public accommodation, and allowed the federal government to enforce desegregation. In 1968 the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. became the catalyst that allowed the Civil Rights Act of 1968, or the Fair Housing Act, to finally pass.

Although the Fair Housing Act made discrimination in housing illegal, the government lacked a concrete way to enforce it. HOME was incorporated in September of 1971 by a group of citizens who wanted to make America’s promise of equal treatment a reality and ensure that every person had the opportunity to live in the neighborhood of their choice. By that winter, our first testing program was in place.

In 1982 HOME won a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision (Havens Realty Corp. v Coleman) that set national precedent and helped expand fair housing enforcement nationwide. This decision upheld that organizations, like HOME, can have legal standing in court.

Since then, we’ve developed comprehensive education and training programs to increase public awareness, encourage conversations, and let people know their rights and how to combat discrimination. This outreach has expanded to include rental properties, mortgage practices, insurance coverage, and more. Our advocacy has helped homeowners, renters, landlords, and real estate professionals know both their rights and responsibilities.

In 1996, HOME challenged the discriminatory practices of one of the largest companies in the homeowners’ insurance industry for redlining African-American neighborhoods. This results of this landmark victory for HOME were two-fold: discriminatory practices were held to be legally and morally wrong and also proven to be harmful for the industry’s profitability. Because of this case, urban residents with the potential to be good customers now have increased access to homeowners’ insurance, and the industry has reaped the benefits of expanding their business into new markets.

Those we advocate for don’t just face racial discrimination. They face discrimination based on sex, sexual orientation, age, nationality, disability, and more. For almost 50 years, we have used our voice to educate, develop laws through legislatures, and even use the court system to protect against unfair housing practices of all sorts.

As we embark on our next 50 years, we’ll continue to expand on the work of our founders and those who came before us to ensure that every Virginian, and every American, has access to fair housing.