Intersectionality, Housing, and COVID-19: Responding to Code Switch’s “What Does Hood Feminism Mean for a Pandemic”?

May 19, 2020

By Mariah Williams.

“Survival is the primary focus, especially for feminists in the hood and rural areas, and for low-income families. Right now, the focus has to be on surviving, on thriving and being able to take care of each other.”

-Mikki Kendall

Recently, I listened to an episode of one of my favorite podcasts, Code Switch. During this episode, called “What Does Hood Feminism Mean for a Pandemic,” Mikki Kendall, author of the new book Hood Feminism joined to discuss how the coronavirus pandemic has exacerbated issues that disproportionately affect women, especially women of color. In Kendall’s examination of the current health crisis she not only discusses how mainstream feminism misses the mark on thoughtfully including intersectionality in advocacy efforts, she discusses how and why housing is crucial to understanding how women of color are disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 crisis.

While the racial disparities of COVID-19 continues to be discussed a great deal, especially as states all over the country begin to re-open, it’s important to also highlight the gender disparities that have been further exacerbated due to the outbreak. Kendall asserts that “mainstream feminists rarely talk about meeting basic needs as a feminist issue, but that food insecurity, access to quality education, safe neighborhoods, a living wage, and medical care are all feminist issues.” Hood Feminism, on the other hand, acknowledges and centers areas that the mainstream movement often overlooks, including poverty, violence, education, race, and the essentials that women need to survive each and every day. It rejects the notion that feminism is simply about equality to men and challenges the movement to think and act more critically in addressing the issues that most women face, not simply a few.

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to expose the extent to which health disparities are not only racialized but also gendered. Kendall connects many of these disparities to housing:

Food Injustice

“If the movement is for all women, you need to be addressing the concerns of all women. And sure, if you are making mid-six figures a year and you live in a very fancy suburb, you may not have to worry about groceries or medical care.”

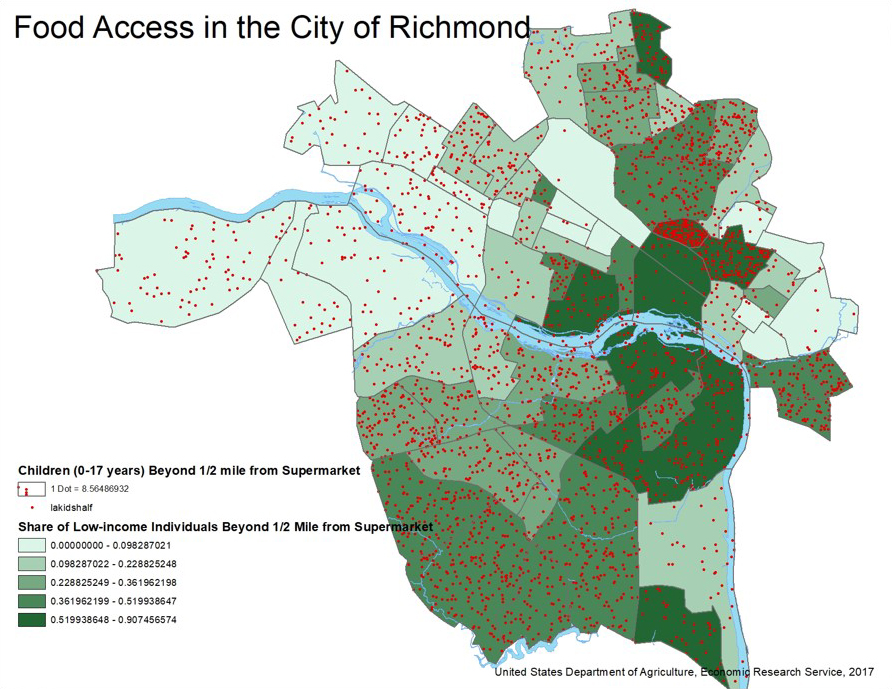

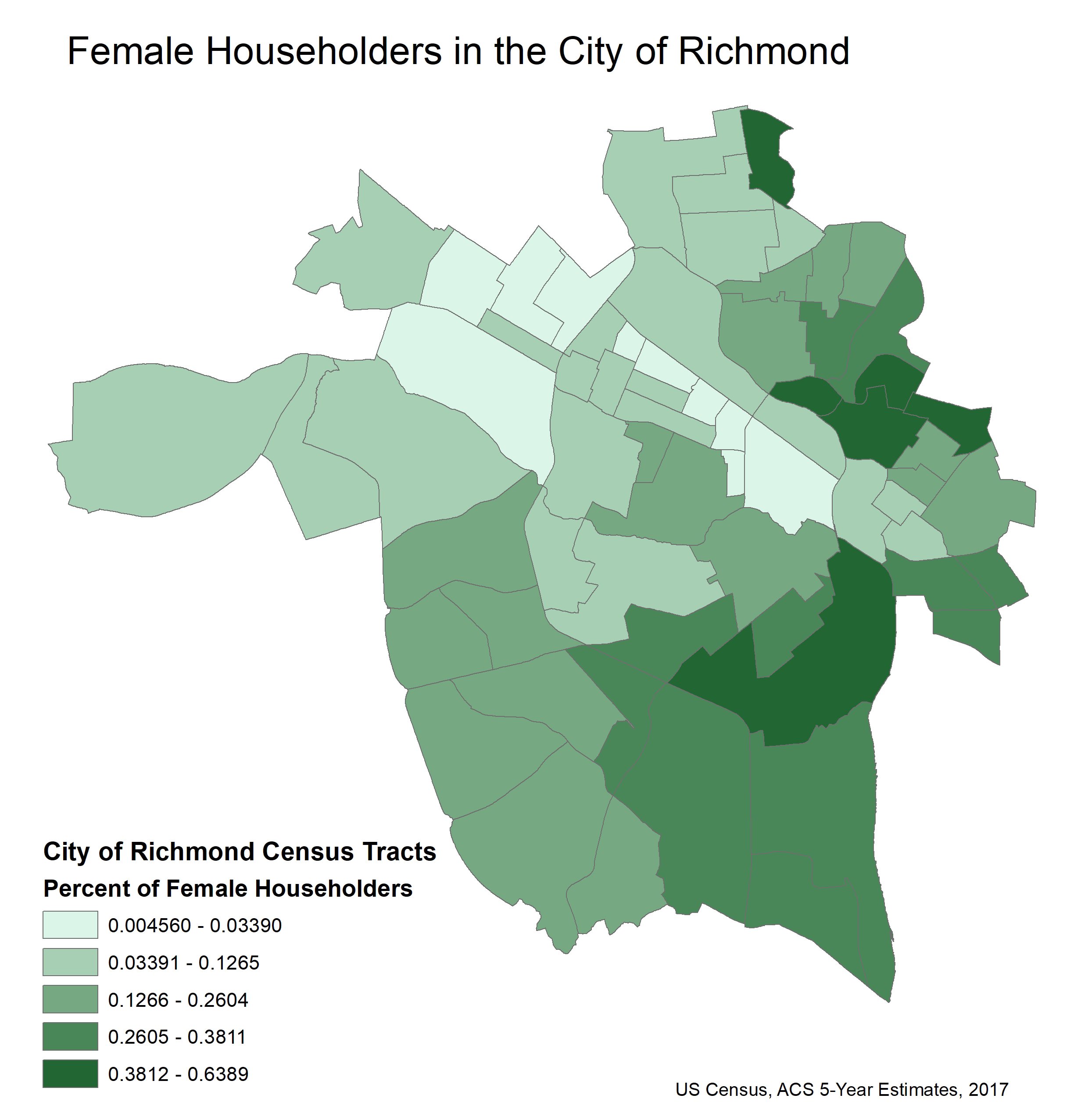

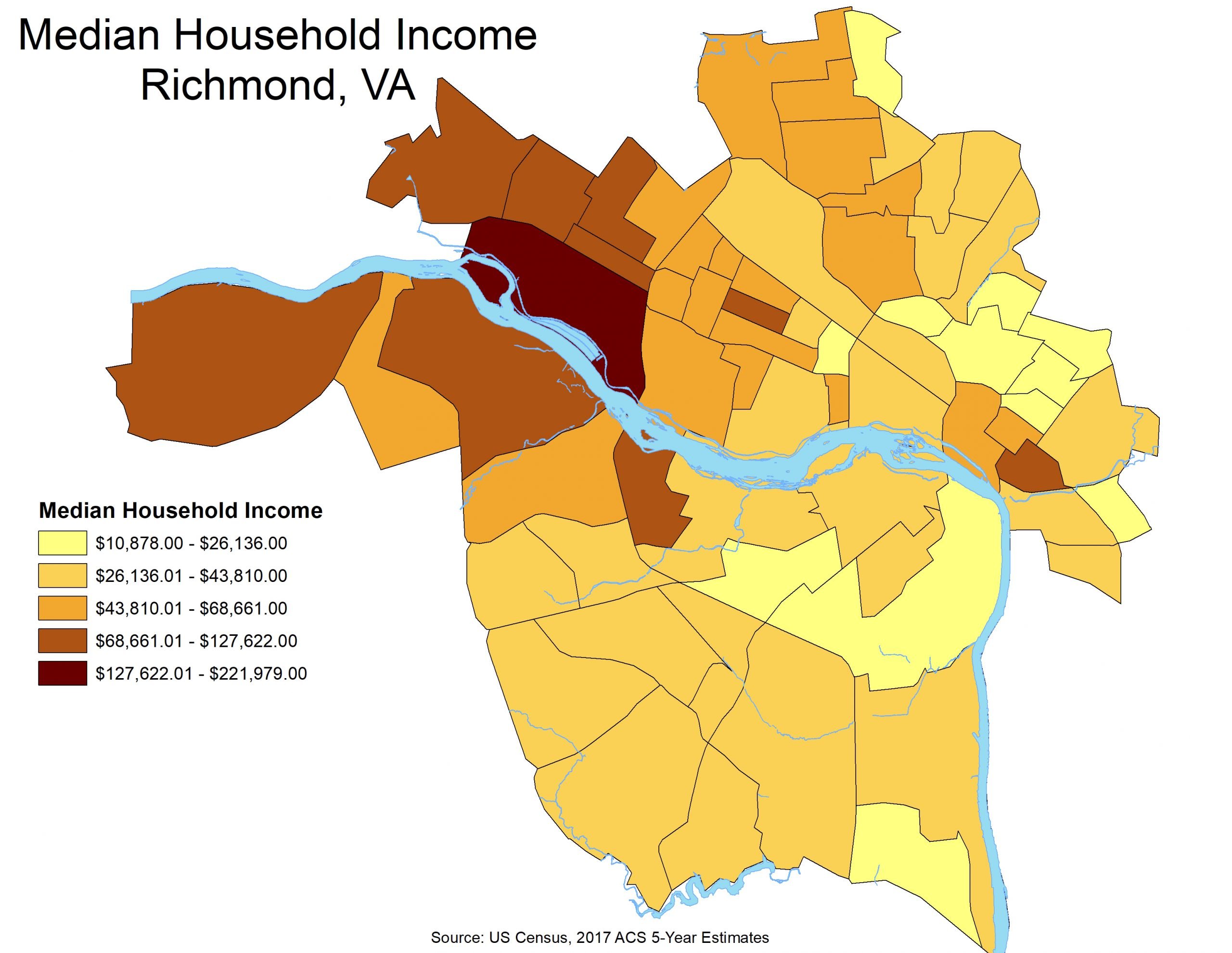

Where we live during this crisis has literally been a matter of life and death. The “stay at home” and “safer as home” orders that many governors across the nation put in place to limit social interaction and flatten the curve privileges individuals and communities that can access things, such as grocery stores, in ways that do not require them to travel far or at all and therefore limits their exposure to the virus. In the city of Richmond, we are well aware of the food injustices that exist. Four in ten Richmonders live in neighborhoods that have few to no grocery stores, forcing them to travel a considerable distance to access healthy food (Food Policy Task Force, 2013). As shown below, many of the city’s neighborhoods with low-income individuals that are more than ½ mile from a supermarket are also comprised of majority female householder families.

Workforce and Employment

Women comprise a majority of the economic sectors that have been hit hardest by the COVID-19 health crisis. According to the National Women’s Law Center, women are two-thirds of the country’s minimum wage workers and are more likely to be the family’s breadwinner. Compounded with the emotional and monetary burdens of childcare and elder care, this pandemic further highlights the need for policies that address the many challenges that women will continue to face during recovery.

Domestic Violence

According to Safe Horizon, 1 in 4 women will experience severe physical violence by an intimate partner in their lifetime. Amid the coronavirus lockdown, police have seen a rise in domestic violence calls. The Richmond Police Department reported a 7 percent increase in domestic abuse incidents from January to April compared to the same time last year. The COVID-19 pandemic not only makes it more difficult for women to access resources to keep them safe, the aftermath of such incidents can result in women’s housing options being limited due to housing policies that penalize them if the police are called.

The issue of housing now and after the crisis is inherently a feminist issue and should therefore be prioritized on feminist agendas because women are overwhelmingly impacted by housing inequalities. More equitable housing policies can be a potential remedy for tackling the racial and gender disparities of the coronavirus. As we work to take care of each other, taking an intersectional approach reminds us that there is no one size fits all for recovery and to center the needs of those that are most marginalized, especial women and people of color.

Back to the Blog