Revisiting Covid-19, Evictions, and Racial Equity

April 8, 2020

By Mariah Williams and Bryan Moorefield.

We all know that when white folks catch a cold, black folks get pneumonia. Simply put, economic hardships experienced by white people may be substantial, but the impact is doubly felt by black Americans who have historically been at the very bottom of the economic ladder. The COVID-19 outbreak and subsequent economic downturn have mirrored what we often see in a national crisis: While some have a social safety net or the private means to ride the crisis out, others are left barely holding on with no such resources to ensure that their lives won’t come unhinged—that wages aren’t lost, food insecurity isn’t exacerbated, and more importantly, that they can remain stably housed and healthy.

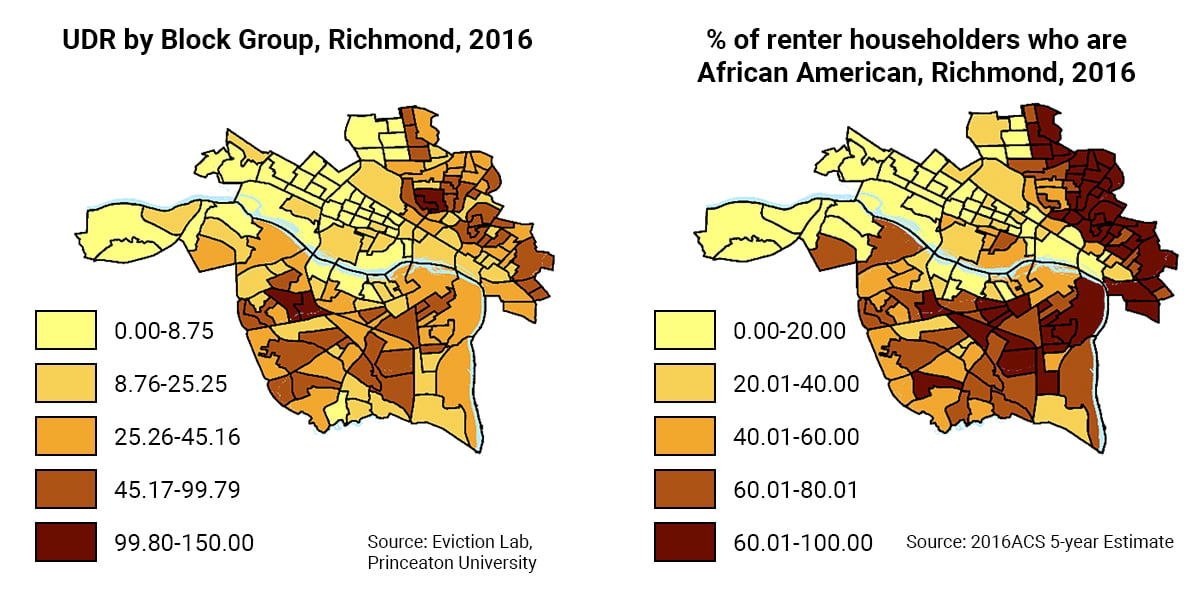

COVID-19 catches Virginia and the City of Richmond in the midst of a pre-existing eviction crisis. Data from the Eviction Lab at Princeton University, which tracked nationwide evictions through 2016, show Virginia and Richmond to have the second highest eviction rates among states and large cities, respectively. Yet the intensity of this crisis has been uneven across our communities. In Richmond, majority-black areas have borne the brunt of the evictions: In 2016, blacks made up a majority of residents in 32 of Richmond’s 66 census tracts. According to the Eviction Lab data, landlords evicted tenants from 17 percent of rentals in the city’s majority-black tracts, whereas they evicted tenants from 7 percent of rentals in the remaining tracts. The effects of these evictions are wide-ranging and life-altering. Besides the loss of one’s home, eviction may disrupt work, school, and neighborhood social connections. This instability also challenges the health of individuals and the surrounding community, in part by pushing the evicted towards crowded or otherwise unsafe accommodations.

Recognizing the need to protect our most vulnerable populations, governments across the nation have acted to ensure that individuals and families remain healthy during the COVID-19 pandemic by passing moratoria on evictions and foreclosures so that people are not forced onto the streets or into shelters. Governor Northam requested and the Supreme Court of Virginia granted a judicial emergency in response to COVID-19. Non-essential, non-emergency court proceedings in all district and circuit courts are suspended absent a specific exemption. This includes a prohibition on new eviction cases for tenants who are unable to pay rent as a result of COVID-19 until April 6. Additionally, on March 24, City of Richmond Mayor Levar Stony announced that no evictions would be executed during the state of emergency. Yet, the question remains what will happen when these emergency measures are up and Richmond institutions return to business as usual.

When we talk about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on communities throughout the state, we must not exclude race from the conversation. As evidenced above, black communities in the City of Richmond are disproportionately vulnerable due to preexisting patterns of inequality, and we know that this trend is not unique to the locality. As state and local leaders continue to work to deploy policies that prevent further fallout from new and existing crises, they must center racial equity and allow their actions to be guided by those that are most at risk. Certainly this pandemic impacts us all, but in Richmond, black neighborhoods, many of which are already ravaged by systemic inequity, have a lot more to lose.

Back to the Blog