防止在健康危机中的住房迁移

2020年4月16日

作者:玛丽亚-威廉姆斯。

"我没有搬迁,"她提醒我说。"我是流离失所。"

这是斯泰西在我问她从新奥尔良搬迁的感受后所说的话。

我没有立即做出区分。前者表明有一个选择。然而,后者则表明没有这样的选择。她被置于不适当的位置,而在这种情况下,这是她的家。

她来自新奥尔良,土生土长,曾在德克萨斯州和北卡罗来纳州生活过,然后在卡特里娜飓风之后定居在北弗吉尼亚州。我当时正在参加住房宣传日活动,很高兴有机会与人们就住房问题进行交流。听到这句话,并试图继续谈话,我回应说,我问了更多关于她在2005年飓风后的生活。她很乐意分享,也很乐意在我说错话时纠正我。与她交谈后,我明白了为什么我的话会刺痛她。

我不知道几周后,我将关注一场全球大流行病的新闻报道,并观察当地政府如何应对健康危机。当我这样做时,我回想起我与这位女士关于流离失所的谈话。

当我们环顾周围发生的变化时,我们中的许多人喜欢认为它们是自然发生的--选择搬家纯粹是基于体验或扎根于新地方的愿望。虽然这是我们中的一些人的特权,但我们必须牢记,搬家并不总是基于选择,有时它是在个人无法控制的情况下被迫的。

列治文市

在过去十年中,里士满市经历了重大变化。当我和在该市南部30分钟车程处长大的母亲交谈时,她经常提醒我,由于该市犯罪猖獗,她曾经是一个避开的地方。这种情况后来发生了变化,里士满正在重新塑造自己的形象,成为一个完全不同的地方,但许多人质疑是以什么为代价?

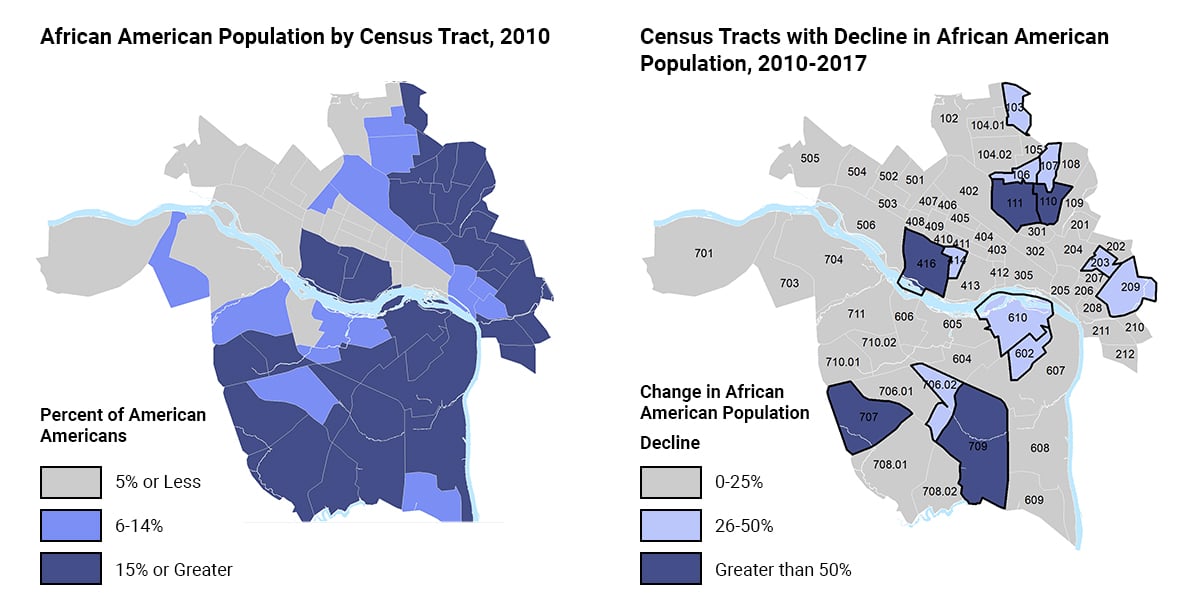

2010年至2017年期间,该市的人口统计学经历了一个转变。虽然该市仍然以非洲裔美国人为主,但仔细观察这些变化,就会发现这些年来,以非洲裔美国人为主的人口普查区变得更白。在一些区,黑人人口减少了15%以上。在一个区,这导致该群体与白人相比,在人口中所占比例较小。

资料来源。美国人口普查,ACS 2010-2017

根据城市实验室的数据,在卡特里娜飓风过后的第一年,黑人居民返回新奥尔良的可能性明显低于非黑人,分别为44%和67%(2015)。虽然里士满的变化是微妙的,但它们触及了我们在试图解决大规模流离失所问题时必须考虑的问题。了解其发生的环境类型以及必须制定的政策,以确保人们能够留下来,或者在卡特里娜的情况下,返回他们的家园,对于减少绅士化的影响和增加获得住房的机会至关重要。

地方政府对COVID-19疫情的反应应该迫使我们所有人更批判性地思考流离失所问题,以及认为流离失所的发生是任何社区所固有的谬论。事实上,我认为,在很大程度上,情况恰恰相反。正是在这样的危机中,必须努力帮助人们留在自己的家中。 正是在这样的危机中,必须牢牢扎根于此,以确保地方政府不参与创造一个推动流离失所的环境。 像那些停止驱逐的政策当然是为了确保家庭今天能够保持安全和稳定的住房,但它们也是为了确保目前的条件不会导致加剧有色人种社区流离失所的模式。现实情况是,如果我们不努力确保家庭在这场危机中能够留在自己的家中,就不能保证危机结束后他们能够返回。

回到博客